Back to Zero

Discovering a Musical Gem

Sometimes life’s zigzags lead you to an unexpected experience that, having had it, you feel suddenly grateful for the very zigzags which may have felt inexplicable at the time.

That’s what happened when I opened my e-mail a couple of weeks ago and found a piece of music in my inbox that was utterly compelling and beautiful, rich and evocative. I knew that I must be one of a small group of people to have heard this piece, and this “exclusive knowing” is driving me to sit here writing this right now, as I wish to create more space for new music I come to know that in my opinion should be known more widely. Hence, installment #1 of Sound Idea.

The piece was Black Mirror (not inspired by the dark Netflix series) by the Estonian composer Toivo Tulev, a circa 18-minute concerto for the improvising trio Hoca Nasreddin and orchestra, premiered by the Estonian National Symphony Orchestra at the 2016 AFEKT International Modern Music Festival, with Michael Wendeberg, conductor. The email was sent to me by Nikolai Galen, vocalist of Hoca Nasreddin. I will get to Nikolai in a bit, but first, Toivo Tulev.

Actually, first, a bit about my chapter in Istanbul.

The story begins in 2010, as I am finishing my doctorate in composition at Harvard University and am going on the academic job market in earnest for the first time. Towards the end of a year of applications, I land two offers, one from Berklee College of Music and the other from Istanbul Technical University’s MIAM (Center for Advanced Studies in Music), a graduate music program started by the well known Turkish-American, post-minimalist composer Kamran Ince and Turkish violinist Çihat Askin. MIAM was founded in 1999 and largely populated with international faculty who had earned doctoral degrees in the United States. At the time I was offered the job, Pieter Snapper and Reuben de Lautour were on faculty teaching composition and sound engineering, and Robert Reigle taught ethnomusicology (all have since moved on).

To provide some context, I write now from the perspective of an Ohioan who left Ohio at 19, believing I would never return, made it as far as Istanbul, lived in Boston, New York City, and Vienna, and somehow managed to land back in Ohio. My four years in Istanbul, from the beginning of 2011 to the end of 2014, constitute a sensory-filled chapter of memory for me now, replete with complex color, smell, commotion, sound, taste, inspiration and conflict. There is much to say about this time, and I plan to write about my experiences of living in Istanbul in a series of future posts; for now, though, I will focus on Black Mirror.

There are a few important puzzle pieces that went into forming Black Mirror, the first being Robert Reigle. Robert is a fascinating human, and I wish more people could know Robert. He is one of the gentlest, most soft spoken, nonjudgmental, vegetarian, and pure humans I have met, and has a monk-like devotion to his art, so much so that his inattention to the base of Maslow’s pyramid is at times shocking. In many ways he embodies the bohemian artist, meditating on what matters to him while being oblivious to the world around him, which unfortunately has at times left him vulnerable to attack.

Robert had lived very poorly most of his life. Prior to coming to Istanbul he lived in New York City in a room that barely fit a bed, working as a manager at a 7/11 to pay his bills. But he described his existence in blissful language, saying that even though it sounds like physical suffering was involved, he was happy to be in touch with the culture and life of the city. Robert had done his main ethnomusicological field work in Papua New Guinea in a village without running water. In Istanbul, many of the music faculty lived in a lojman (state housing), which was nearly free and somewhat made up for our meager salaries, and while I was shocked and appalled at the condition of the lojman, Robert seemed quite at peace with the living quarters, as it may have very well been a step up from the hardships of his previous living situations.

When I lived in Istanbul I was eager to eat out, enjoy the food and the neighborhoods and experience the city. Robert, on the other hand, would leave from the lojman on the one shuttle that would take us to the MIAM campus, which was in the bourgeois neighborhood Nisantasi, about 40 minutes from the main campus, which was located in the uninspiring business center Maslak. The shuttle left at the crack of dawn, and then Robert would sit in his office seemingly all day, breaking for a 2 lira (dirt cheap) cafeteria lunch and then return to the lojman on the shuttle that would leave at the end of the day. From my perspective it seemed like a very restricted, lonely life.

I don’t think it was lonely for Robert, though, or if it was, he seemed at peace with his solitude. Apart from being an ethnomusicologist, Robert was an active avant-garde saxophonist and aficionado of contemporary music from all nooks and crannies of the world, and spent much of his time downloading music and building an immense personal library filled with exotic and esoteric discoveries. One of the joys of my day was pausing outside of Robert’s office, which was located in the same suite as mine, and listening through the door to evocative and strange sounds emerging from the other side of the wall. Inevitably, Robert would open the door and give me a pop quiz. I nearly always failed, the answer being something like, “this is a young Lithuanian composer whose piece for chorus glissandos up a semitone over the course of half an hour.” I was in awe of Robert’s breadth of knowledge.

He was a Scelsi devotee, and was personally in touch with many important composers of our time, among them the Romanian spectral composers Ana Maria Avram, who wrote a solo piece for Robert, and her husband Iancu Dumitrescu. Robert performed with Dumitrescu’s ensemble Hyperion in Romania, Paris, Belgium, London, and Geneva. Robert was first and foremost concerned with timbre, an issue that served as glue between his ethnomusicological work and his interest in contemporary music, and he, with colleagues, had organized an important international spectral music conference at MIAM in 2003, which hosted a wide range of composers, including Tristan Murail, Joshua Fineberg, Iancu Dumitrescu, Ana Maria Avram, flutist Helen Bledsoe, Argento Ensemble with Michel Galante, conductor, and Cornelia Fales, ethnomusicologist.

The times when Robert would break his course of daily study and teaching often involved him performing on the saxophone. He was an avid improviser of new music, and I had the pleasure of hearing him around town at venues such as Kadiköy’s Gitar Cafe. One of the groups he performed with was “Hoca Nasreddin,” which consisted of, in addition to Robert on saxophone, Nikolai Galen on vocals and Serkan Sener on Kaval.

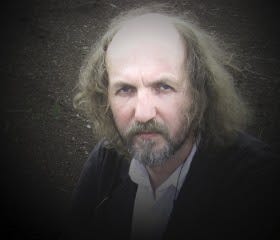

This was improvisation of the free and wild sort, coming out of a noisy, Cageian aesthetic, and privileged extended techniques. Galen, who was tall and lanky with wild hair, and gave off a Mick Jagger-esque vibe, had taught himself an array of extended vocal techniques and would perform them theatrically, conveying a taught intensity in his performances. I wondered how his vocal chords could sustain the growls, shrieks and meanderings that he put them through. Serkan, who I knew least well, played kaval, a Turkish flute, which added a beautiful, airy timbre to Hoca Nasreddin. Together, this trio would revel in a huge range of sound, from the ethereal to the explosively violent, mixing gestures in a compelling and gripping manner.

The group is named after Nasreddin, a 13th-century Sufi who has come to be known for his anecdotes and humor. “Hoca” in Turkish means teacher, and is used as a sign of respect. Naming themselves after this character is perhaps a nod to the depth and playfulness of the group’s improvisations. Apart from Galen, the group’s personnel appears to have been fluid over the years; below is a recording featuring Galen, Reigle on tenor sax, Kevin Davis on cello, and composer Turgut Erçetin on electric guitar.

Hoca Nasreddin is the second important ingredient in this story; the third is Toivo Tulev. I had the chance to meet Tulev when he visited Istanbul (was it 2012?) to give a masterclass. He had been invited by Eren Arin, a composer who was studying at the conservatory and who now is on faculty at the Ondokuz Mayis University in Samsun, Turkey, near the Black Sea. The conservatory is a separate institution from MIAM, though located steps away, and focuses on traditional Turkish music. Composition there was much more conservative than the avant-garde tendencies that flourished at MIAM.

Tulev, in my memory, was tall, balding and had long hair and intense but kind eyes. He gave a masterclass, and I have one specific memory of him sitting at the piano and playing a student’s composition very slowly, listening intently to the notes ring. It was a striking image, because the material at the moment seemed relatively unremarkable to me, but Toivo’s attention to it was indeed remarkable: he seemed to be slowing down time and listening to something inaudible, waiting to uncover a tendency, an answer.

Tulev presented his music at MIAM, and I remember thinking that his music was beautiful and deep, but there was also something reserved about it. It is perhaps challenging for Americans to hear music like Tulev’s without having some background thought of Arvo Pärt (the most ubiquitous Estonian composer). The two composers’ music do share some qualities: a stretched time frame, a sense of rootedness, depth of feeling, hints of tonality, if not direct modality/tonality, and an air of mysticism. Yet Tulev’s music is stripped of the filmic, wall-papery associations I have with some of Pärt’s work, and generally moves in more directed, dramatic arcs.

In a recent conversation with Robert, he told me that he and Tulev met around that time and connected over their shared interest in spirituality and Scelsi. Robert invited Tulev to come to a rehearsal of Hoca Nasreddin, and Tulev obliged. Afterwards, Tulev told Robert that he would like to write for them: this was the kernel for Black Mirror.

I also had a chance to ask Robert about Black Mirror’s notation and how much was left open to improvisation. I was especially curious about this because Galen is completely self taught and cannot read music, and there are moments in the piece when the trio performs a line synchronously with the orchestra. How did Galen achieve this?

Robert explained that everything was notated specifically, with the exception of a few passages of “not very free” improvisation. Galen learned to read music just well enough to be able to follow the cues of the score and know when to enter. Beyond that, he practiced with midi that Tulev generated, memorizing his part.

In the end, the result of Black Mirror is much more than the sum of its very respectable parts. Each of the two components, Hoca Nasreddin and the orchestral music, provide something essential that complements the other: the orchestral writing creates a deep ambience and dramatic soundscape that fills space; Hoca Nasreddin provides surface flair and wild timbral and gestural variety that I find missing in some of Tulev’s other music.

It’s a synchronous piece. Its creation depended on serendipitous meetings in Istanbul of an American ethnomusicologist/improvisor and an Estonian mystic/composer (not to mention the serendipitous meetings of the members of Hoca Nasreddin themselves). I happened to be in the orbit of these moving parts and am grateful for that twist of fate.

Around two minutes into the piece, Galen enters, speak-singing “back to zero.” This piece takes me “back to zero” in creating a soundscape novel and powerful enough to force me to experience it with fresh and alive ears.

thank you Adam!

you’re very kind to us

small comments

I hardly used the midi at all; I toyed with it but it didn’t really work for me; mainly I was able to follow the score thanks to Robert and Serkan’s patience with me, and also thanks to the sessions we did with Rueben (also wonderfully patient)

and I figured out how to break down the score in a way that became more or less digestible for me (and Toivo showed me a few tricks as I recall)

still when it came to performance, my ability to get the score in synch (and tune) with the conductor and musicians was hit and miss - and none of my score is improvised; I suppose there’s a stage to come, if we ever get to perform the piece a few more times, where I would feel free to devote myself to interpretation and not to structure; as it is, there’s quite a lot of tension between the two which I hope I at least got away with but…

the hardest aspect for me was performing with the orchestra and conductor; it’s the nature of the orchestral system that rehearsals are minimal and the conductor rules (all my singing life, I’ve had the pleasure to be more or less the one the musicians had to follow…)

at one stage, I resigned as I thought I just can’t do this; but it seems that I rescinded my resignation…

extended vocal techniques - quite a lot of study went into my own development of extended vocal techniques, mainly but not only with various members of the Roy Hart Theatre, though I think what I do is mostly the result of self-exploration coupled with the realisation a long time ago that force must be used vary sparingly if one’s not to wreck one’s voice; an another aspect of my approach is I don’t strive to imitate a certain vocal sound, I allow other sounds (say from Central Asia or from all kinds of avant-garde vocal work) to open my imagination but then let my body physicalise that imagination as it will

Nikolai Galen