Shrouded in darkness, a rounded talking head in black in white, with thick, artsy glasses, and a salt and pepper beard looks directly into the camera, “we need to have a frank and serious discussion about program notes: (pregnant pause) we got ‘em” (the entirety of the conversation). He goes on, “It’s just like the programs we hand out during our live concerts, only digital,” cut to “digital!” flashing across the screen in ‘80s video game lo-fi font. The speaker’s clear and measured tone and dry, acerbic humor create a striking contrast to the otherwise ominous, film noir quality of the production.

This talking head belongs to Timothy Beyer, composer and artistic director of No Exit Ensemble, and these speaking introductions (of which there are several at this point, found on No Exit’s Youtube channel) exhibit a mixture of high artistic intent and surgical comic timing that offers an entree into Tim’s world.

To enter further into Tim’s world takes some digging, however, as his online presence is limited; he has no website, though you can read his bio on No Exit’s home page. I met Tim when I ran into a friend, the composer Hong-Da Chin at a Cleveland Orchestra concert where he was in attendance with Tim. Hong-Da was in town as a guest composer with No Exit, and I invited Hong-Da to come speak at my composition seminar at Kent State the next Monday. He was without a car, and Tim drove him to KSU, where we met up for burritos at the legendary Taco Tantos (one of the last truly hippie hangouts in Kent) before heading to seminar.

I was already aware of No Exit Ensemble, one of Cleveland’s most active new music ensembles, now in its 12th season. No Exit has consistently programmed diverse music of the highest caliber since its inception. As an educator in the area, I also had quickly become aware of No Exit’s dedication to working with emerging composers. As just one example, they have been instrumental in ensuring that young composers have continued to receive performances during Covid-19: this year they partnered with Transient Canvas and Noa Even and premiered new works by composers from Kent State, Cleveland State, and Baldwin Wallace Conservatory.

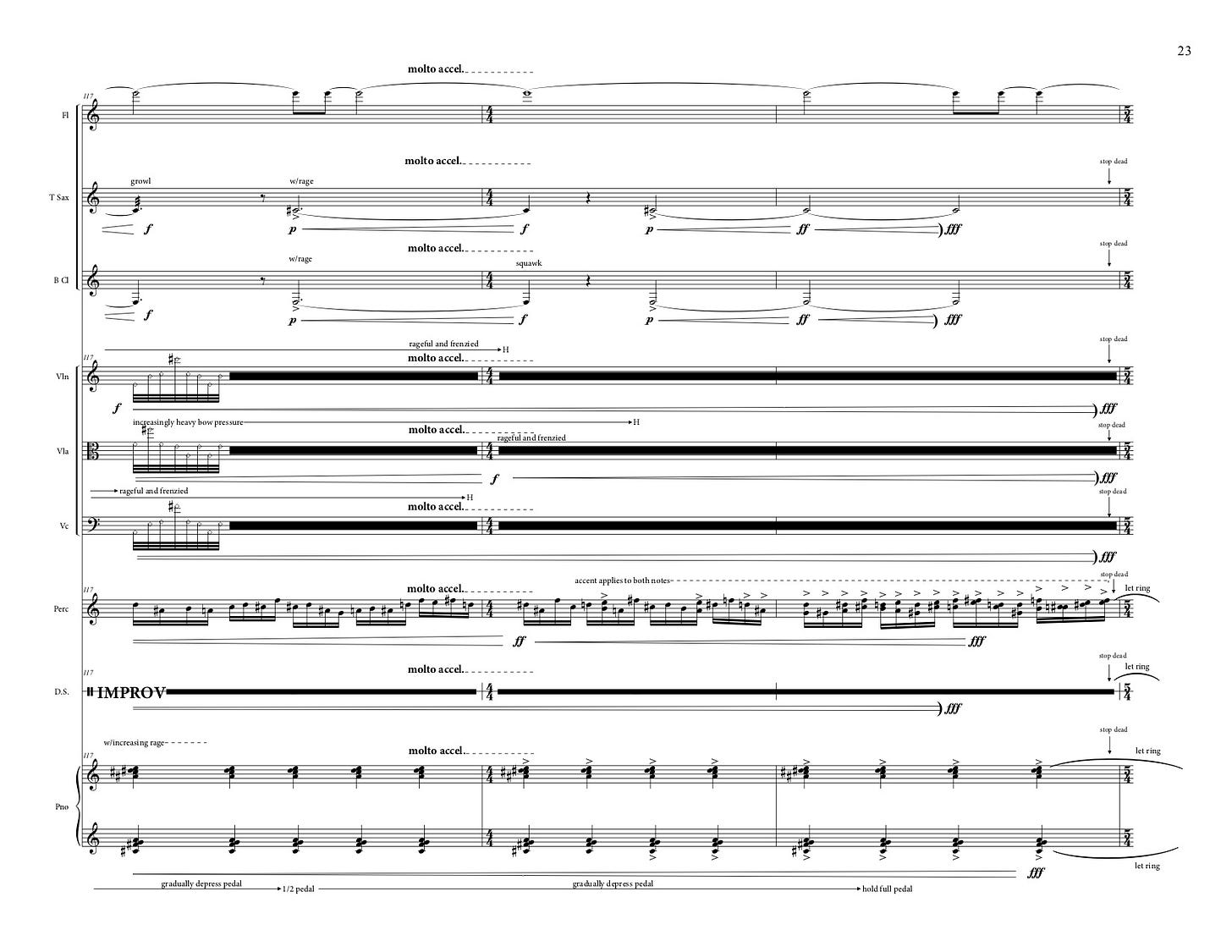

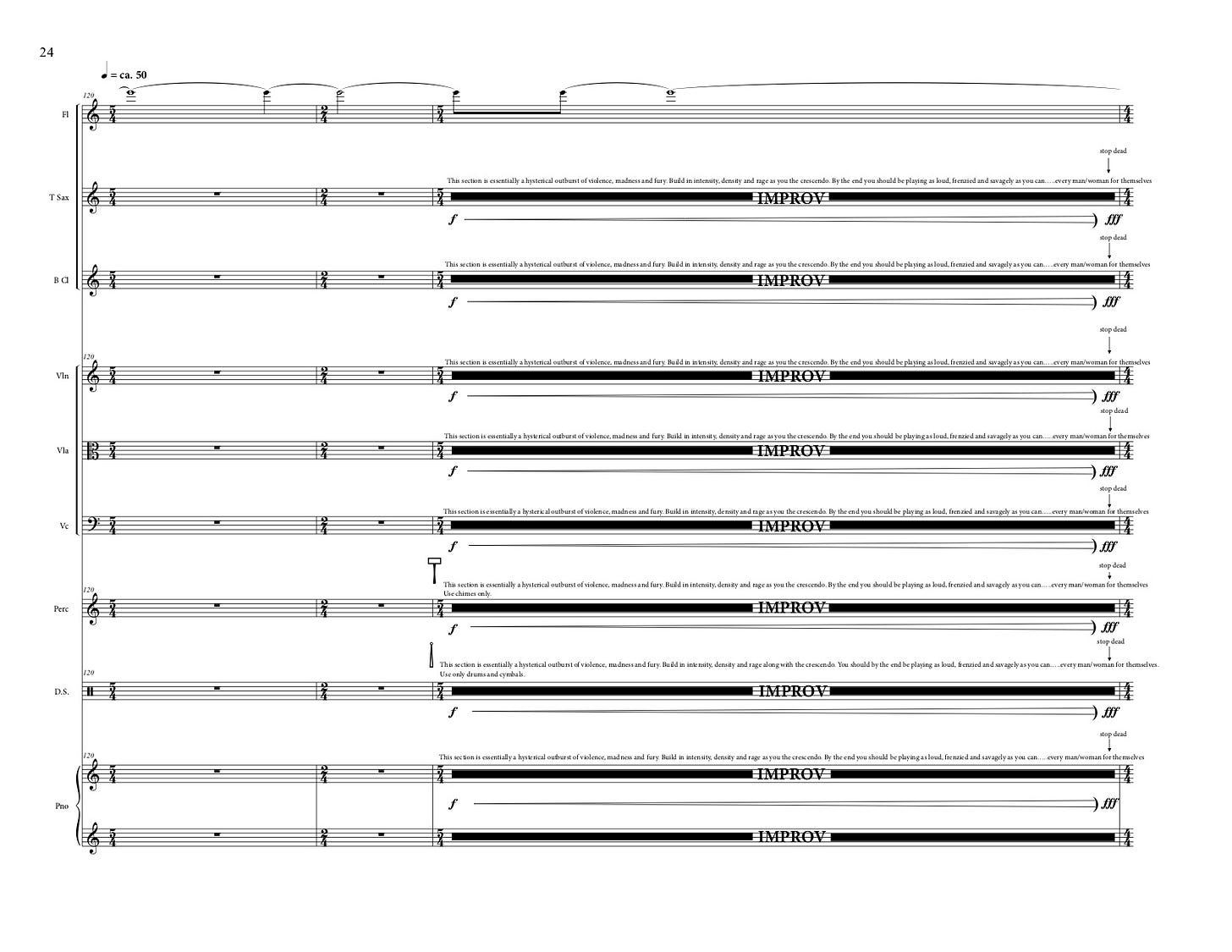

Back to the No Exit virtual concert, Tim’s introduction is in fact preceded by another introduction, a blast of full-bodied sound, consisting of pulsating, dense piano chords that gradually accelerate, with a myriad of other instruments pulling out spectral harmonic detail. This rich sonority reaches a cadential pause, leaving cymbal resonance and a quiet flute note suspended in the air, and then moments later we are whisked into what sounds like a sped-up tape rewind, sound flying through the air and wiping the slate clean.

When I first heard this introduction as part of No Exit’s first virtual video premiere on 10/02/2020, I texted Tim, asking what the hell this amazing sound was, not realizing it was his music. What gripped me immediately was the density, the orchestration, and perhaps most importantly, the harmonic sensitivity: there was clearly an astute ear organizing this verticality into a dissonant but highly resonant structure. It reminded of the opening bell sonority of Tristan Murail’s 1980 orchestral work Gondwana, a favorite verticality of mine, that is also highly dissonant (inharmonic) and resonant. So naturally, I asked Tim to send me the score, and he obliged.

It turns out that this introductory music is the climax of a 2018 work entitled She Was My Only Child, composed for No Exit New Music Ensemble and Patchwork (Noa Even, saxophones and Stephen Klunk, percussion). Consisting of flute, saxophone, bass clarinet, percussion, drum set, piano, violin, viola, and cello, these groups create a unique ensemble that, in the history of contemporary music, feels like either an expanded Pierrot ensemble or a reduced chamber orchestra.

As striking as the piece’s sonic climax is Beyer’s formal restraint: this twelve-minute work essentially unfolds one sonority that excruciatingly moves from stasis to activity, culminating in the aforementioned dense blast of sound. After this moment of intensity, the music lingers, frozen again.

There are fragrances of other composers here. Morton Feldman’s music crosses my mind in relationship to the widely spaced harmonic field that runs throughout the work. There are unpredictable repetitions in this music, also reminiscent of Feldman, though Feldman generally repeats pitch patterns while changing rhythmic figurations; here, instruments swell or change parameters (eg. from non vib. to vib.) coloring the music. These kinds of delicate color changes call Scelsi to mind, and the swells and bell-like harmony evoke spectral music. But these are only fleeting associations, this music exists in a world of its own.

Of particular note is the work’s stasis, especially with regard to its harmony. Other composers would succumb to pressure to vary the notes more (the traditional academic composition advice). I can imagine it would be important for a composer like Murail to show his métier and create some kind of progression or teleology. Beyer’s piece, on the other hand, by doggedly not varying the core harmony, commits itself to sitting with an uncomfortable emotional state and watching it incrementally thaw from frozen pain into an angry growl over the course of its duration.

Indeed, the title of the work and its formal arc make me wonder if the piece is an enactment of catharsis. I hear the climax as an outcry, a yell of aggression, and the quiet aftermath as devastated resignation. The title speaks to the trauma of loss, which only reinforces this interpretation.

The discomfort of the work is not only communicated by the piece’s emotional content, it also arises due to the actions required of the performers. Most notably in this regard is the flute part: the flutist plays a pp E6 for the entire duration of the work, a seemingly simple action that requires intense focus and physical stamina. The composer writes as an instruction to the flutist “like still air, non vib.” While every other instrument progressively performs increasingly varied material, the flutist must remain unmoved, un-vibrating, embodying an emotional thread that is unable to transform, remaining stuck in time. Apart from the final three strikes of a chime, this flute E is the last sound we hear, symbolizing the idea that some pain may not so easily be released.

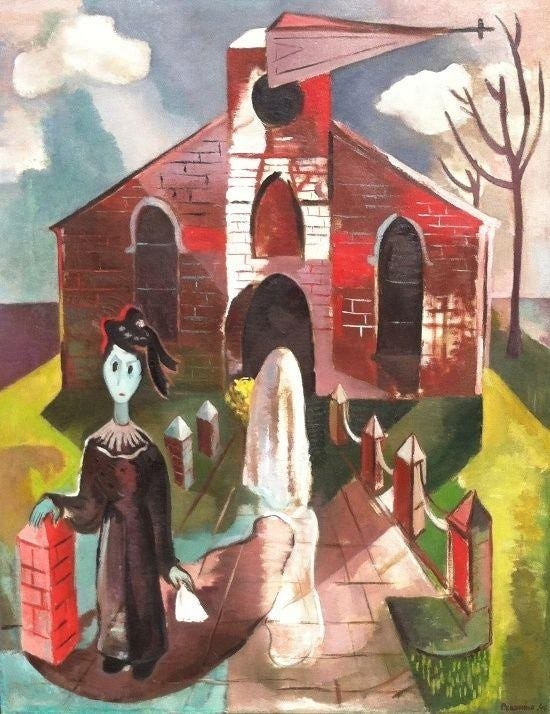

I asked Tim about the title, and he explained that he had been in a relationship with a woman who had a daughter, with whom he had been very close. When the romantic relationship ended, Tim’s relationship with the woman’s daughter became complicated, a loss that remains painful to this day. The title of the work comes from this painting:

About the connection of this painting to the musical work, Beyer writes:

Let me start off by saying that in my mind, much of the aesthetic and sensibility of my piece came from this painting. There's a lot that conveys this aesthetic: the color palette, the distorted figurative representations and elements of the overall composition. It's clear that the mother is in mourning, the visual manifestations of this are almost Victorian. To me, the depiction of the 'toppled' church steeple indicates that in the face of such loss there is no solace nor salvation to be found in religious dogma. You're stuck with the sorrow, there's no escape from it, it becomes a part of you.

What really hits me is the depiction of the deceased child. Rather than a ghastly apparition, the dead daughter is covered in a sheet like a child's halloween costume. At first glance, it almost seems whimsical, but it is utterly devastating. The 'costume' is literal, in that it is a ghost, while also being an embodiment of childhood and is likely a representation of the child's personality and predilections, perhaps even a recounting of an actual incident in the little girl's life. By depicting the child in this way, the loss is made real. The fact that the 'ghost' casts a shadow shows that in some way the dead daughter (or internalized embodiment or memory thereof) is quite real, as if to exist in the physical world. Depicting this 'ghost' in such a fashion also drives home the notion that she will forever be a child, will never age or grow up, permanently frozen in memory as she was at death. She is dead. The dead are nothing. They're dead. It's the memory of them that may survive (a grieving parent). To quote my own bad poetry..........There is no longer truth, only memory.

In several wide-ranging, darkly funny conversations and through a talk on his work, I learned that Beyer had come to formal composition study relatively late in life (in his mid-twenties). He was always deeply committed to a life in music, and he spent his earlier years composing and performing as the trombone player in the group Pressure Drop. An experience of meditating on the atrocities of the Holocaust—Beyer is Jewish—moved him to turn his attention more to composing, as he felt that popular outlets would not allow him to express the depth of emotion he was experiencing. Beyer enrolled at Cleveland State University where he completed his undergraduate and Master’s degrees with mentors Andrew Rindfleisch and Greg D’Alessio. CSU was also where Beyer met James Praznik, composer and co-director of No Exit.

I asked Beyer about trauma and loss (also exemplified by Beyer’s Amputate series). In stark existentialist remarks, Beyer talked about how humanity wouldn’t be around much longer, and of the pointlessness of human existence. We live, we make, we die, there is no ultimate meaning. But then Beyer would laugh, a sense of humor peeking through the despair. Was the humor simply a coping mechanism?

Beyer explained that composing for him often involves a lengthy process of meditating on pain. He forces himself to stare at devastating images, sometimes for hours at a time, in order to engender a state from which he can create most directly about such experiences. He compared this to method acting—he feels he has to fully inhabit a frame of mind in order to work. Beyer has taken it upon himself to stare unflinchingly at the darkest parts of humanity and to give voice to these experiences.

Beyer is a force for good in NE Ohio, dedicating himself to bringing people together to make idealistic art, and working to provide young composers with abundant performance opportunities. He thrives on taking a stand for music he believes in and for emerging artists. I can’t help but be amused by the contrast of Beyer’s bleak outlook of humanity and his own positive community-building activities: even though humanity is doomed, Beyer is compelled by a tikkun olam sensibility to leave the world a better place than how he found it (even if he believes this won’t make a drop of difference).

Beyer may have stared into the void and seen an abyss, but ironically, this darkness may be the very force providing him with a sense of purpose.